The spiritual traditions of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples are deeply rooted in animism—a worldview that acknowledges the presence of numerous invisible entities that influence both nature and human life. This belief system encompasses deities, ancestral spirits, the souls of the dead, and other supernatural forces.

At the heart of these traditions are shamanism and spiritual mediumship. In many Indigenous groups, certain individuals are seen as intermediaries between the human world and the spirit realm. Known as shamans, they are believed to receive messages from spirits, perform healing rituals, and interpret omens. In Paiwan culture—which shares ritual similarities with the Rukai in the north and the Puyuma in the east—shamans may be either men or women.

Rituals and ceremonies structured the social life of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples, marking harvests, seasonal changes, hunting successes, and military victories—reflecting a way of life deeply shaped by culture, survival, and territorial conflict. As such, rituals and ceremonies played a vital role in celebrating major events such as harvests, seasonal shifts, hunting achievements, and war victories.

Each Indigenous group in Taiwan has its own ritual structure and cultural codes. Religious objects belonging to Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples are exceptionally rare and difficult to locate. In the years following World War II, under the growing influence of modern civilization and Jesuit missionary efforts, many sacred objects were abandoned, hidden, destroyed, or altered. Unlike daily utilitarian items, few survived the cultural upheavals of the postwar period. This exhibition allows us to discover some of the religious instruments used by Paiwan* tribal shamans.

Most of these boxes began to appear in Indigenous culture in the early 20th century. Prior to this, people used leather bags made from deer belly or rattan boxes. These divination boxes are made by hollowing out the center of a solid block of wood to form a square container, then decorating the front face with carved patterns. The artistic value of the box lies in its carvings. Typically, a fine hemp rope net is placed over the opening at the top of the box, and the edge is fitted with rattan rings to hold cords for tying the net shut. These boxes are the result of collaborative work: men carve the wood and perform the sculpting, while women craft the upper net and rattan elements. Some boxes have carved wooden lids instead of nets, but only among the Puyuma. Inside, they contain small knives, betel nuts, pieces of pig skin representing the whole animal, acacia leaves, and glass beads.

Divination knives are an essential component of the divination box, used during ritual practices. Each knife serves a specific function depending on its shape—cutting betel nuts, slicing meat, or carving wood.

Sacrificial vessels, such as offering trays, are exceptionally rare in museums or among collectors of tribal or primitive art because, as sacred religious items, they were considered untouchable by outsiders and were long hidden from view.

Additionally, the rapid spread of foreign influences—especially the introduction of Christianity and Catholicism—led to the rejection of many ritual objects. Once central to spiritual life, they were increasingly viewed as obsolete and often discarded or destroyed.

Among the Paiwan, the most commonly used offering vessel is a rectangular wooden tray with a handle. During healing rituals performed by shamans, pieces of meat—usually from wild boars or deer—are placed on these trays. Larger versions are also used during festivals and community ceremonies.

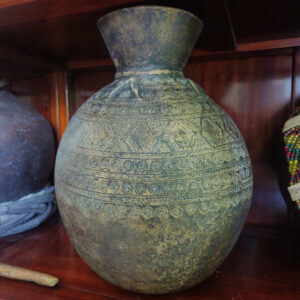

In Paiwan culture, sacred pots hold deep spiritual and symbolic meaning. They are traditionally placed inside niches carved into the slate walls of noble houses (see photo below). These pots are considered one of the three great ancestral treasures of the Paiwan people, alongside glass beads and the sacred knife.

According to oral tradition, the Paiwan trace their origins to a sacred union between a serpent and a pot—two powerful symbols of life, protection, and continuity. Only noble families possessed these sacred vessels, which were venerated as heirlooms passed down through generations. Far from everyday use, these pots were reserved for the most important ceremonies—such as offerings to spirits, healing rituals, and the grand five-year festival (Maruvuk).

Some pots were permanently sealed and believed to house ancestral spirits or protective forces. Others were placed on household altars or buried during funerary rites, emphasizing their sacred role in both domestic and ritual contexts.

Due to their spiritual significance, these objects were rarely shown to outsiders. Many were hidden, destroyed, or lost, especially with the arrival of foreign religions and the decline of traditional practices. Today, surviving examples are exceptionally rare and deeply respected, embodying both the material heritage and spiritual worldview of the Paiwan people.

Paiwan sacred pots are also rich in symbolism. Based on their carvings, pots may be classified as male, female, or hermaphroditic. While this classification is complex and has been studied in academic research, a simplified interpretation suggests that pots adorned with small circular motifs are considered female, while those bearing sacred snake designs are male. Pots displaying both motifs are regarded as hermaphroditic.

The visible breaks often found on the handles or rims of these pots are intentional. When a son or daughter married and left the family home, the parents would break off a piece of the pot and give it to the child—symbolizing a continued spiritual bond with the ancestral home.

Divination pots used by Paiwan shamans are generally small in size so they can be easily carried during rituals. They often have rounded bases that prevent them from standing upright—an intentional design that emphasizes their spiritual role rather than any practical function.

Shamans use these sacred vessels to invoke the gods, as the Paiwan believe the pot serves as a dwelling place for deities. In ritual contexts, it becomes a spiritual channel between the human world and the divine.

The purpose of this prayer tablet is that on the first day of the five-year festival, at sunrise, the chief of the village holds this tablet and calls on the Dawu Mountain to invite the highest god to descend to the earth, and then the five-year festival can begin. It is an important art piece that is closely related to the study of the primitive religion of the Paiwan people. The round tablet is carved with a hundred-step snake, which is very primitive. From this sacrificial vessel, we can also see how closely the beliefs of the Paiwan people are related to the hundred-step snake!

Authentic bronze knives are extremely rare and are believed to date back to the Tang or Song dynasties, possibly originating from northern Vietnam—though this remains uncertain. These knives fall into two categories: those held by noble families, and those used by shamans in rituals. They also symbolize masculine strength and authority.

There are approximately ten known types of bronze handles associated with these knives. The iron blades were considered less important, as they were prone to rust and regularly replaced.

* The term “Paiwan” is sometimes used here as a general label to refer to three very similar tribes: Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma.

This exhibition presents a selection of 18 pieces from our collection, currently available for sale.